by Jeff Gogué

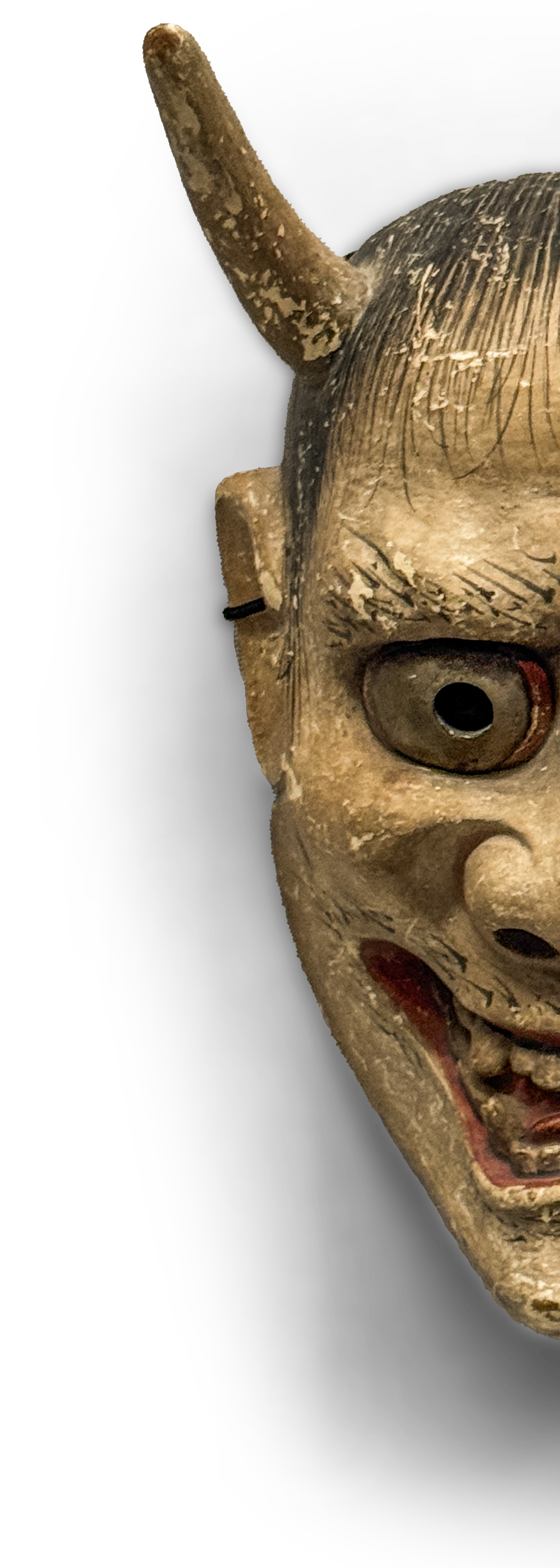

A Kitsuneja mask on loan from Wakayama prefecture, in Tokyo… about tradition, innovation, and the responsibility we have.

Staring into its eyes on the last day of my twentieth trip to Japan. Kitsuneja … a fox-snake hybrid from the Edo period. I didn’t come looking for it.

My first time at the Tokyo National Museum was twenty days after the huge earthquake and tsunami of 2011. Seared in my memory is an old Japanese man sitting alone on a bench under the massive maple tree just in front of the monolithic staircase leading to the main entrance.

He was bent over, head in his hands, and sobbing. It was a living Time Magazine cover shot. My body flooded with chills; the broken, cracked, empty water fountains on the grounds also telling of the havoc wreaked less than three weeks prior.

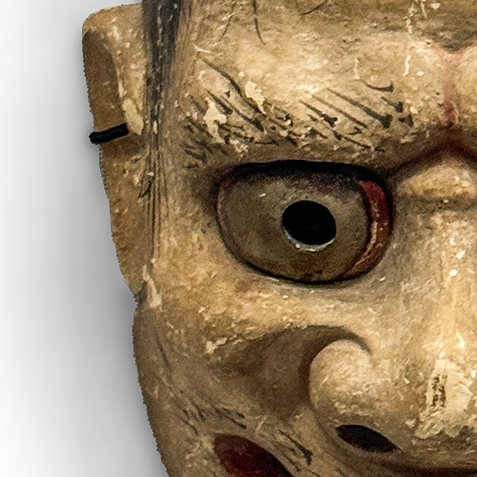

These haunted eyes stared as hollow as the feelings during that trip. The label said 18th…19th century, carved by someone whose name is lost to time. A nobody.

My first thought was Hannya. The same tension in the mouth. Anguish and anxiety, but the energy was different. Less emotional. Less tragic. More… primordial. Hannya is heartbreak curdled into rage. Kitsuneja feels like nature simply being, not feeling or thinking but responding. Triggered by movement, like a predator in the night.

We talk about tradition like it’s in a museum … something polished and protected, hanging there with good lighting and a small plaque. But everything in that room started as a risk. Some artist, somewhere, decided to make a mask that didn’t exist the day before. They didn’t ask permission. They weren’t trying to replicate some perfect version of the past. They were trying to tell a story in the moment they were alive.

This Kitsuneja mask isn’t “the iconic one.” Not the celebrity mask with centuries of commentary trailing behind it. This one was carved for a reason we’ll never know, for a performance we’ll never see, by a person we can’t name. And yet it survives … still here, still staring back, outliving everyone else involved.

The anonymous carver. Maybe they’d seen Hannya masks and thought, “What if the fear didn’t come from sorrow? What if it came from something older? Something animal?”

Tradition comes from a long series of people trusting their instincts. It’s what has been passed on but also what has been infused, expressed, and interpreted.

We inherit forms… patterns, symbols, shapes… but tradition isn’t the form. It’s the willingness to reach into the unknown while standing inside something familiar. The lineage isn’t a set of rules. It’s an ongoing conversation.

Standing there, responsibility tapping my shoulder… it’s what we feel as artisans, tattooers, painters, musicians, and anyone who makes something. We’re not just repeating what came before. We’re choosing how it keeps breathing. Every mark, every decision, every “what if” becomes part of the story that someone else might discover long after we’re gone.

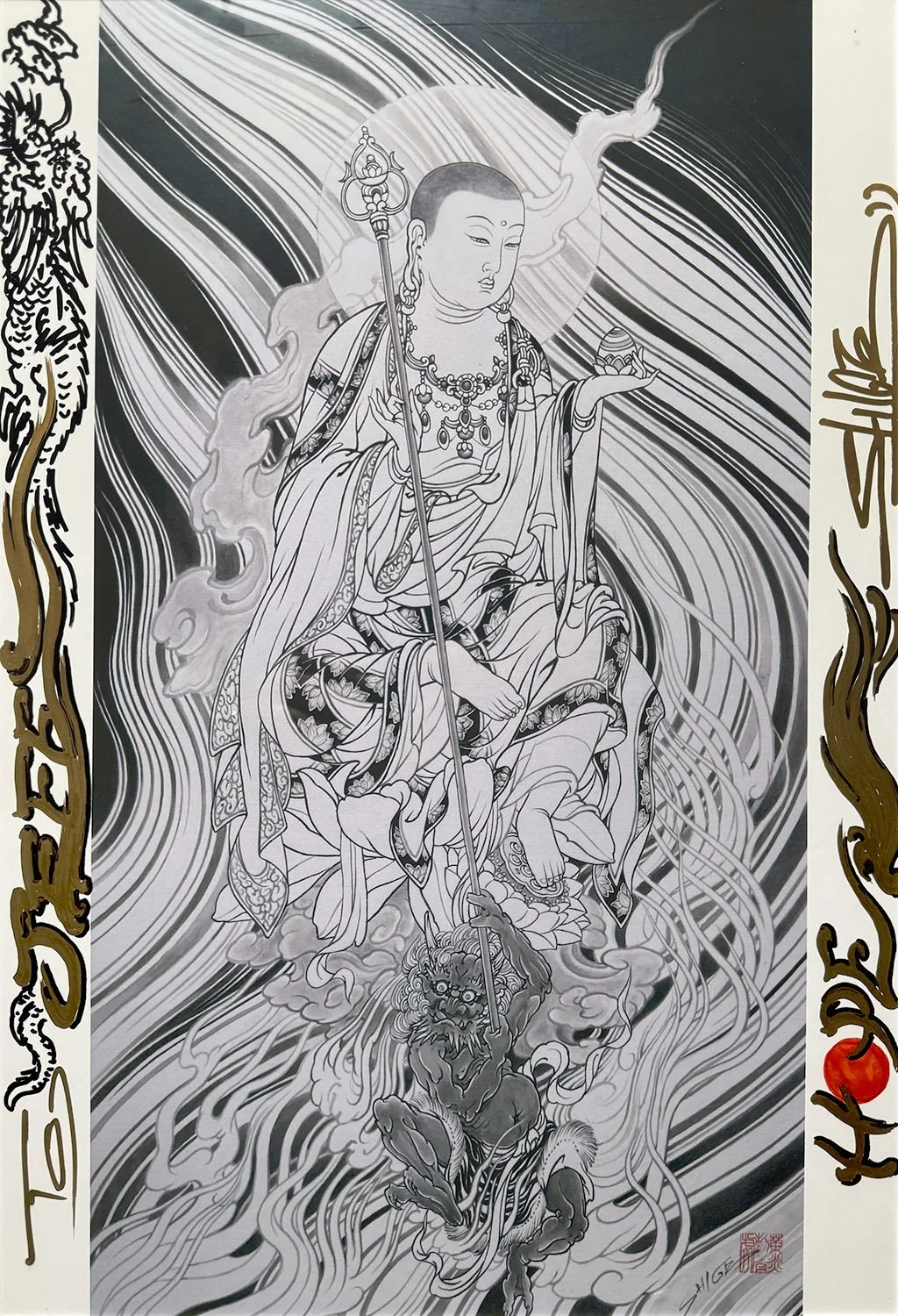

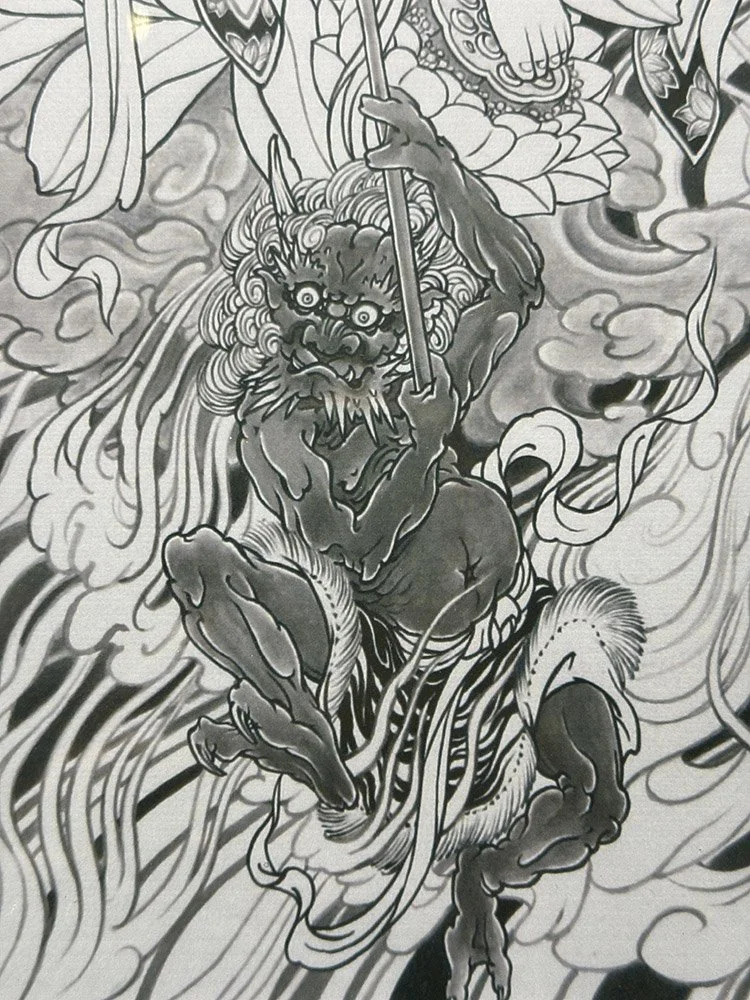

Shige-San once showed me a painting he made of Jizō Bosatsu (地蔵菩薩), the young monk-like bodhisattva who descends into hell to free the suffering, rising back toward the light, staff (shakujō) in hand. Clinging to the bottom of the staff was a demon reaching for a way out too. I asked him if that was part of the original story. Grinning, he said, “No. I add.”

That Kitsuneja mask reveals the old masters weren’t traditionalists. They were experimenters. Innovators. People who weren’t afraid to mix fox and snake, fear and humor, sacred and strange. They carved things that made sense to them, for their own time and their own audience. And now we treat their work like fixed monuments … but they were alive when they made it.

And so are we.

Tradition isn’t a dead thing. It’s not preserved behind glass.

It’s a river, and we’re standing in it.

We get to influence the current.

That’s the opportunity … and honestly, the obligation … for anyone creating right now. We don’t honor tradition by freezing it. We honor it by participating in it. Adding to it. Twisting it. Questioning it. Expanding its vocabulary the same way that the unnamed Edo-period carver did two hundred years ago.

I walked away from the mask thinking about that river. Thinking about how many anonymous hands shaped the world I learn from. Thinking about how someone, someday, might walk into a gallery or a studio or a tattoo shop and have that same moment with something I made.

We don’t get to control what survives.

But we do get to leave our own footprints along the path we go down.